Documentation from Sally Raab's Perpetual Inventory in TRUCK's +15 Project Window at Arts Commons

Monday, October 5, 2015

Friday, August 21, 2015

Tuesday, July 21, 2015

Wednesday, July 15, 2015

ESSAY: Before Prospero's Cell

Group exhibitions are often difficult to talk about in a way that does justice to the complex and distinct works that have been brought together within them. In conceiving a model for thinking about these exhibitions, and this one in particular, my thoughts swing to archipelagos. In The Radicant, the metaphor of an archipelago is touted by Nicolas Bourriaud as “the dominant figure of contemporary culture,"[1] as a mode of thinking that rejects totalizing systems in favour of a network of conversing autonomous entities. As a collection of islands, an archipelago is comprised of discrete physical bodies with distinct topographies and ecologies, however, they often share collective traits or elements: cultural features, for example, or the climate, objects that float among them on ocean currents, seed pods that drift on the wind, creatures that swim and long for the experience of other terrains. And so it often is with exhibitions, including this one: ideas arrive, ricochet, are shared, and depart.

Joe Bérubé’s series of drawings, Inventory of an Unknown Island (2012-2015), is a sharp-eyed catalogue of flora, fauna, and fragments of human activity. Though they resemble natural science illustrations torn from an anthropologist’s observational field notebook, these objects have no origin in a particular place. The island from which they come is one of conjecture, a place not yet known. The drawings offer a strange perversion of the scientific methodologies of direct observation and documentation. Instead, they present a speculative taxonomy; in them the imagined and the real coexist in an incongruous space. By utilizing taxonomic organization and technical aesthetics Bérubé gestures to our perennial impulse to neatly categorize the world. The documentation of the imagined object, however, problematizes the language of discovery and the act of claiming knowledge. The blurring of the real and unreal reveals the ineffable qualities of the world and the ambiguity involved in coming to know something.

The human impulse toward order and categorization is one borne out of a desire for control. In his short essay “Desert Islands” (1953) Gilles Deleuze muses on the psychogeographic relationships among islands, humans, and the imagination. He articulates our need for philosophical normalcy as a fundamental condition for living: "Humans cannot live, nor live in security, unless they assume that the active struggle between earth and water is over, or at least contained…humans can live on an island only by forgetting what an island represents." [2]

Sandy Grant’s large-scale oil paintings pull back the cover on this assumed normalcy; they reveal the folly of our strategies to impose harmony and order and our tendency to isolate ourselves from the natural world. These images pick at the edges of our efforts to control the chaotic, the mental barriers we raise against the unsettling wild, and the lies of dominance that we tell ourselves. They depict day-to-day experiences rubbing up against, or operating adjacent to, the hidden natural world in unsettling and unnerving ways. Grant raises the corner on the deliberate, formalized edges of humanity’s impositions to reveal the things that lurk just out of sight: the hissing in the shadows of shaded hedgerows, the irrational reptilian fear of submerged logs beneath our plump little toes, and the threat of tremendous and uncontainable natural disasters exacerbated by our human carelessness and excesses. In spite of our best efforts, these unplanned and unsettling edges of existence have a deep and profound effect on us all: in each of us skulks the frightening spectre of our fundamental impermanence.

Natasha Alphonse, Joe Bérubé, and Sandy Grant are occupied by encounters with the (un)familiar, by questions about what makes us human, and by intense curiosity about the complex linkages between the surrounding environment and ourselves. Leaning from a steep slope draws their work together in a speculative dialogue about the mysterious affinities, existential wonderings, and inescapable relationships that affect us all.

Essay by Shauna Thompson

1. Nicolas Bourriaud, The Radicant, trans. James Gussen and Lili Porten (New York: Lukas & Sternberg, 2009), 185.

2. Gilles Deleuze, Desert Islands and Other Texts, 1953-1974, (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2004), 9.

About the Writer:

Shauna Thompson is Curator at the Esker Foundation, Calgary. Previously, she worked with Walter Phillips Gallery, The Banff Centre; Justina M. Barnicke Gallery, and YYZ Artists’ Outlet, both in Toronto; Doris McCarthy Gallery, Scarborough; as well as the Art Gallery of Mississauga. She holds a master’s degree in Curatorial Studies from the University of Toronto as well as a master’s degree in English from the University of Guelph.

- See more at: http://www.truck.ca/events/772#sthash.mugF34aH.dpuf

Mysterious relationships are also at the centre of Natasha Alphonse's work. Through intuitive arrangements of collected found objects (natural and/or synthetic, chosen for their affinity of colours and material qualities, and often paired together) Alphonse creates arranged forms in a simple economy of balanced, site-specific gestures. Each component of a sculptural pairing actively influences and relates to the other: they are mutually dependent. The objects at once exist as they are, but also adopt human-like qualities through spatial relationships and physical dialogue. There is something truly enigmatic about our affinity to these objects; we find ourselves implicated in an empathetic response as we

project ideas, narratives, and characteristics upon them. We imagine a mutual recognition and dependency exists and we come to understand the components of the installation – including our presence – as parts of an inextricable whole.

Essay by Shauna Thompson

1. Nicolas Bourriaud, The Radicant, trans. James Gussen and Lili Porten (New York: Lukas & Sternberg, 2009), 185.

2. Gilles Deleuze, Desert Islands and Other Texts, 1953-1974, (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2004), 9.

About the Writer:

Shauna Thompson is Curator at the Esker Foundation, Calgary. Previously, she worked with Walter Phillips Gallery, The Banff Centre; Justina M. Barnicke Gallery, and YYZ Artists’ Outlet, both in Toronto; Doris McCarthy Gallery, Scarborough; as well as the Art Gallery of Mississauga. She holds a master’s degree in Curatorial Studies from the University of Toronto as well as a master’s degree in English from the University of Guelph.

Wednesday, June 10, 2015

ESSAY: One With The Strength of Many

“Mystery is not about traveling to new places but about looking with new eyes.”

— Marcel Proust

In Heraldry the purpose of the Motto is to formally summarize the motivation and guiding principles of a social group.[1] The original Coat of Arms of the City of Winnipeg first bore the motto “Commerce, Prudence, Industry.” This declaration reflected the guiding principles of the Settler culture of the territory and the lasting legacy of colonization to the region. The City Motto was replaced in 1972 with the current Crest bearing the Latin "UNUM CUM VIRTUTE MULTORUM" or “One with the strength of many,” a reflection the complex identity and history of Winnipeg, firstly as “one city formed of people of all races; and secondly, … one city formed from many cities.”[2] It is this complex history and narrative that the Winnipeg based artist Evin Collis explores in his exhibition “Commerce, Prudence, Industry.” As a Winnipegger, a Manitoban and a Canadian, of a combination of Scottish, French, English and Métis origins, Collis delves into the “complexities and vulnerabilities of [not only the history of Winnipeg, but the whole of] Canadian history, identity and mythology. Collis’ works focus on re-interpretation and amalgamation of the histories interwoven with satire, folklore, social commentary and classical allegory.”[3]

One of Romanticisms enduring legacies is Nationalism, and Nationalism lies at the very heart of the colonialist project. In his 2008 novel “A Fair Country,” Canadian author John Ralston Saul writes about the ‘triangular reality of Canada,’ rooted in the founding nations, the First Peoples, Francophones and Anglophones. Saul argues that the entity of Canada has a malleable identity instead of the monolithic identities of other states. Indelibly shaped by the above trifecta over the past three centuries, with Aboriginals playing a quintessential role.[4] Saul also makes it clear that the recognition of this fundamental influence is lacking, but necessary to define a contemporary Canadian identity. Arguably, the denial of these essential and complex interactions, in particular the disavowal of the Indigenous influence has been a defining feature of Canada’s colonial project of building a white settler nation on Indigenous land.[5] Complexities are pushed aside in favour of romantic notions of destiny, settlement, commerce, and nation building.

In his large-scale paintings and mixed media sculptures Collis grabs the wibbly wobbly malleable thing that is Canadian identity and myth by the soft rubbery parts and shakes it free from its settled state. Influenced by the High Renaissance, allegorical painting, the Mexican Muralists, Graffiti, and Folk art, Collis takes on the icons of Canadiana. The fur trade, the transcontinental railroad, and the expansionist colonization of the west, become grist for the artistic mill in an exploration how history is qualified, quantified, and quadrated. Making use of such implements of satire, allegory, humour, Collis “conjures differing notions of icons, heroes, and monumentalism while questioning our enduring relationship with history," and from this emerges a new mythology.

Myths and Icons recur throughout the works. The mixed media sculpture “Hydra Goose,” references the classical Greek myth of the Lernaean Hydra, a multi headed poisonous water serpent so terrifying that when a single head is cut off two immediately grow back to take its place. The “Canadian” Hydra Goose - like Canadian history – is a multi headed creature and vain attempts to trim and obscure it through a singular perspective only allow it to become stronger and a greater threat to that perspective. The Hydra Goose recurs in the large scale painting “The Assiniboine Odyssey,” lurking in the quagmire of the Assiniboine river bottom as the ship, reminiscent of the “Raft of the Medusa” under fauvist skies, grinds by.

Collis’ works combine the best elements of satire and allegory designed to elicit either humour or consternation. Satire serves as an answer to the romantic notions of a singular view of Canada, a modus operandi that Collis is well aware of in his explorations of identity and nationhood. Satire and humour exist in direct conflict with romanticism, often dismissed as irrelevant, frivolous, or unworthy of serious consideration.[6] This romantic reading of satire fails to recognize the critical capacity of the imagery or irony in Collis’ milieu. In satire reality dominates over ideology, and ironically this is often involves a parody of romantic mythical forms, for in satire irony is militant.[7] The “natural” soft focus is relinquished in favour of a gritty reality unmasked.

Referencing the German expressionists, and with an eye to the works of painters such as Jorg Immendorff’s (Café Deutschland history painting series) combined with the grittiness and unabashed tone of cartoonist such as R. Crumb or Spain Rodriguez, Collis takes on even the touchiest of subjects. The core ideologies that were/are historically at play, namely religion (Christianity) and spiritualism are explored in works such as “Rail Yard Resurrection” or “Red River Pieta,” in a manner that is uniquely Collis’ own. The monumental mounds perhaps reminiscent of artists such as Phillip Guston include the detritus of history and the colonialist project juxtaposed in the most unexpected ways. When first encountering these works, the combined images, icons, and idols, made me laugh out loud, but after the initial flame of humour, the slow burn of thoughtful contemplation began. A masterful demonstration of that old adage, “first make them laugh, then make them think.”

Essay by Renato Vitic

1 Webster’s Revised Unabridged Dictionary. . The ARTFL Project. The University of Chicago. Chicago, Retrieved 15 April 2015

2 Hartemink, Ralf. . Heraldry of the World. Ralf Hartemink. Retreived 10 April, 2015.

3 Collis, Evin. Artist Statement. Calgary, TRUCK, 2015.

4 Saul, John Ralston. A Fair Country: Telling Truths About Canada. Toronto: Viking, 2008 : 174

5 Thielen-Wilson, Leslie. White Terror, Canada’s Indian Residential Schools and the Colonial Present: From Law Towards a Pedagogy of Recognition. Toronto: University of Toronto, 2012 : 4

6 Martin, Rod A., ?The Psychology of Humor: An Integrative Approach?. Academic Press, 2007: pp. 27–8???

7 Herring, David. Northrop Frye's Theory of Archetypes Winter: Irony and Satire . Retreived 10 April, 2015.

- See more at: http://www.truck.ca/events/763#sthash.w447QdBg.dpuf

Saturday, May 30, 2015

DOCUMENTATION: The Laboratory of Toxic Maturation

Documentation from Alyssa Ellis' The Laboratory of Toxic Maturation in TRUCK's +15 Project Window at Arts Commons

Thursday, April 30, 2015

Wednesday, April 1, 2015

ESSAY: An Exhibition Essay on Kyle Beal's Exhibition

“Jokes are products of human ingenuity that at their driest and most refined, fall within the domain of art. Yet many people – even people blessed with a rich sense of humour – loathe them.” [1]

Kyle Beal’s exhibition Roulette is an installation that asks the viewer to explore a hallway lined with doors; to literally linger in a passageway. In the 1967 film Playtime Jacques Tati creates a humorous critique on modernity as the film follows two separate characters throughout a thoroughly modern Paris continuously absorbed by the sites, sounds, and gadgetry of the large metropolis. Throughout the film we can’t help but find humour in the discombobulating and angst Mosieur Hulot (played by Tati himself) experiences as he goes about his day. The female protagonist, an insouciant American tourist who haphazardly discovers Paris on her own terms, contrasts this. The two main characters’ days overlap throughout the film juxtaposing playfulness and disorientation. Beal’s hallway of doors reminds us of the ‘fun house’ and the disorientating yet playful interventions it flaunts. Like Tati – Beal draws on simple oddities of modernity and the unsuspecting disorientations we experience and discover as we move through space and time. Once inside the hallway we are surrounded with multiple closed doors - each having their own function giving us a curious but sublime feeling of alienation.

Beauty can be far too limiting as a term for an art object, so we instead look at the object’s aesthetic value. An object like Beal’s hallway is interactive and the observer transitions into an active aesthetic engagement. Our experience within the hallway is characterized by the condition that we do not ask anything of the hallway itself but take pleasure in the contemplation of the playfulness it boasts.

In the video Poke in the Eye/Nose/Ear (1994) by Bruce Nauman (USA) the artist presents us with a very detailed and closely cropped image of an eye, a nose, and an ear to be interpreted at face value (pun intended). Each considered image of the artist as a disembodied subject spotlights the individual act of a self-inflicted literal poke in the face. Nauman’s intent for the viewer accentuates the unusual situation as the art, instead of a more traditional product as the art, giving the experience as a whole more importance than the individual actions taking place on screen. In Beal’s exhibition Roulette we too are looking at art as an activity and less as a product. By creating the physical hallway this object’s function becomes less about its literal properties; instead being the experience the viewer has deciphering its purpose. The contrast between sense and nonsense becomes significant with the humorous artefact we are left with from this experience.

Freud theorized that a nonsensical joke references the time of our childhood – when our innocence didn’t need humour to feel happy. In contrast laughter can too relate to hopelessness, frustration, and more specifically alienation. When we run out of emotions to express our feelings laughter is often the bodies last form of expression. A frustrated laugh is a lot different than the innocent laughter of a child. The importance of humour as a coping mechanism for these themes is illustrated in the discoveries behind each of the doors. These physical objects are recognizable comedic tropes that take a slapstick approach into finding place in the zeitgeist of innovation. Which one should we open, and what awaits us on the other side?

As we hurtle through time, modern design and technologies attempt to bring us closer together making it easier for personal connections, repairing a social fabric while at the same time unraveling it. Feelings of alienation have never been so prominent and unsuspecting. There is nothing funny about this except that it can be made funny. “Jokes are a medium for fantasizing about what must be avoided in reality, a way of laughing off our cruel, irrational, and aggressive instincts.” [2] Looking back at the mishaps of our failures a sense of humour brings light to these dark places. ☺

“You Are the Clown who put the ugh in Laughter” – Richard Wilbur

Essay by Jeremy Pavka

----------------------------------

[1] Holt, Jim. Stop Me If You've Heard This: A History and Philosophy of Jokes. New York: W.W Norton, 2008. 125. Print

[2] Holt, Jim. Stop Me If You've Heard This: A History and Philosophy of Jokes. New York: W.W Norton, 2008. 41. Print

Kyle Beal’s exhibition Roulette is an installation that asks the viewer to explore a hallway lined with doors; to literally linger in a passageway. In the 1967 film Playtime Jacques Tati creates a humorous critique on modernity as the film follows two separate characters throughout a thoroughly modern Paris continuously absorbed by the sites, sounds, and gadgetry of the large metropolis. Throughout the film we can’t help but find humour in the discombobulating and angst Mosieur Hulot (played by Tati himself) experiences as he goes about his day. The female protagonist, an insouciant American tourist who haphazardly discovers Paris on her own terms, contrasts this. The two main characters’ days overlap throughout the film juxtaposing playfulness and disorientation. Beal’s hallway of doors reminds us of the ‘fun house’ and the disorientating yet playful interventions it flaunts. Like Tati – Beal draws on simple oddities of modernity and the unsuspecting disorientations we experience and discover as we move through space and time. Once inside the hallway we are surrounded with multiple closed doors - each having their own function giving us a curious but sublime feeling of alienation.

Beauty can be far too limiting as a term for an art object, so we instead look at the object’s aesthetic value. An object like Beal’s hallway is interactive and the observer transitions into an active aesthetic engagement. Our experience within the hallway is characterized by the condition that we do not ask anything of the hallway itself but take pleasure in the contemplation of the playfulness it boasts.

In the video Poke in the Eye/Nose/Ear (1994) by Bruce Nauman (USA) the artist presents us with a very detailed and closely cropped image of an eye, a nose, and an ear to be interpreted at face value (pun intended). Each considered image of the artist as a disembodied subject spotlights the individual act of a self-inflicted literal poke in the face. Nauman’s intent for the viewer accentuates the unusual situation as the art, instead of a more traditional product as the art, giving the experience as a whole more importance than the individual actions taking place on screen. In Beal’s exhibition Roulette we too are looking at art as an activity and less as a product. By creating the physical hallway this object’s function becomes less about its literal properties; instead being the experience the viewer has deciphering its purpose. The contrast between sense and nonsense becomes significant with the humorous artefact we are left with from this experience.

Freud theorized that a nonsensical joke references the time of our childhood – when our innocence didn’t need humour to feel happy. In contrast laughter can too relate to hopelessness, frustration, and more specifically alienation. When we run out of emotions to express our feelings laughter is often the bodies last form of expression. A frustrated laugh is a lot different than the innocent laughter of a child. The importance of humour as a coping mechanism for these themes is illustrated in the discoveries behind each of the doors. These physical objects are recognizable comedic tropes that take a slapstick approach into finding place in the zeitgeist of innovation. Which one should we open, and what awaits us on the other side?

As we hurtle through time, modern design and technologies attempt to bring us closer together making it easier for personal connections, repairing a social fabric while at the same time unraveling it. Feelings of alienation have never been so prominent and unsuspecting. There is nothing funny about this except that it can be made funny. “Jokes are a medium for fantasizing about what must be avoided in reality, a way of laughing off our cruel, irrational, and aggressive instincts.” [2] Looking back at the mishaps of our failures a sense of humour brings light to these dark places. ☺

“You Are the Clown who put the ugh in Laughter” – Richard Wilbur

Essay by Jeremy Pavka

----------------------------------

[1] Holt, Jim. Stop Me If You've Heard This: A History and Philosophy of Jokes. New York: W.W Norton, 2008. 125. Print

[2] Holt, Jim. Stop Me If You've Heard This: A History and Philosophy of Jokes. New York: W.W Norton, 2008. 41. Print

Tuesday, March 24, 2015

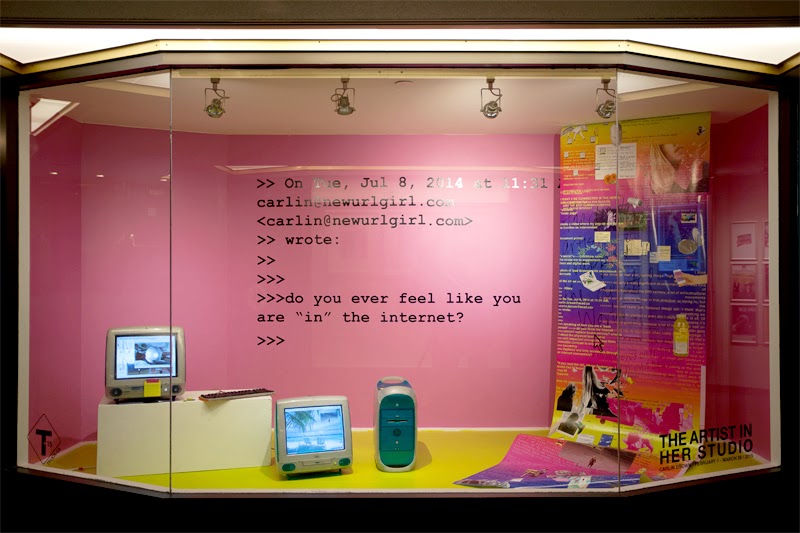

DOCUMENTATION: The Artist in Her Studio

Documentation from Carlin Brown's The Artist in Her Studio in TRUCK's +15 Project Window at Arts Commons

Friday, February 20, 2015

Saturday, February 7, 2015

U-Hall: The Urban Canada Foto Kollective

Urban Canada Foto Kollective's Wild Life:

The Urban Canada Foto Kollective (UCFK) are photographers who are interested in the cityscape, the ebb and flow of life on the street, and the ways people affect their environment. UCFK aims to make photography more present in Calgary, and continue a critical dialogue about image making and urban life.

In past exhibitions, UCFK has examined themes dealing with the connections and disconnections of urban living a simultaneous yearning for wild nature amidst vain attempts to civilize it. With Wild Life, UCFK have turned their attention to the animals in our urban environment.

In this exhibition Angela Inglis’ photographs are a continuation of her practice of documenting urban scenes captured with a point and shoot approach while travelling through London, San Diego and on home turf, Calgary. This time her images bear witness to the undulating movement of seagulls and pigeons as they rise and fall for bread crumbs and cheezies; winter geese nestled in an industrialized area of the Elbow River; and a sombre encounter with a woodland creature provides a comic yet endearing glimpse into a

moment in time.

Melody Jacobson’s photographs also come from travels to Spain, London and in her new hometown of Vancouver. The subjects in her photos are pensive and watchful, peering at the viewer like the crow on the wire, or the girl in the street scene in Barcelona. The puppy in this photo looks content with her sleeping master, however, the pity on the skateboarding boy’s face speaks volumes to the uneasiness society has with nonconforming behaviours, such as the men sleeping in the street. Her photos also highlight the animal nature of humans, with office workers sitting by the Thames River in London on their lunch hour, by juxtaposing a similar scene with ducks resting by a swimming pool closed for winter. The photos are printed on Canadian birchwood, further merging themes of nature with street photography.

Cat Schick’s contribution to this exhibition is different from what she’s done before in that it is more than straight photography. Her pieces are 11x14” color photographs with images of animals cut out of them, combining the street art vernacular of stencil with the medium of photography. The animals chosen are all those who live or have lived on the prairies and are literally cut out of or removed from the city landscape – those that were here before us and have adapted to the urban environment (rattlesnake, bat, hare, bird) and those who have been driven further and further away, only to be challenged and possibly killed when venturing back into the city (cougar, moose, deer). The buffalo has not been seen on the prairies for many decades and is slowly being reintroduced back into national parks in some provinces. The work aims to question our relationship to animals and our ability to share the environment with other beings. As a collective of female photographers observing our urban environment, UCFK consciously creates images to remind us of the subtle power of nature. The images examine the durability and fragility of these moments, when the city noise quiets and we’re struck by the beauty of an image of nature: where we came from and where we’re going all in the same moment.

Cat Schick’s contribution to this exhibition is different from what she’s done before in that it is more than straight photography. Her pieces are 11x14” color photographs with images of animals cut out of them, combining the street art vernacular of stencil with the medium of photography. The animals chosen are all those who live or have lived on the prairies and are literally cut out of or removed from the city landscape – those that were here before us and have adapted to the urban environment (rattlesnake, bat, hare, bird) and those who have been driven further and further away, only to be challenged and possibly killed when venturing back into the city (cougar, moose, deer). The buffalo has not been seen on the prairies for many decades and is slowly being reintroduced back into national parks in some provinces. The work aims to question our relationship to animals and our ability to share the environment with other beings. As a collective of female photographers observing our urban environment, UCFK consciously creates images to remind us of the subtle power of nature. The images examine the durability and fragility of these moments, when the city noise quiets and we’re struck by the beauty of an image of nature: where we came from and where we’re going all in the same moment.

UCFK is Angela Inglis, Melody Jacobson, and Cat Schick, who have been working together as a collective since 2009. Street photography is our focus, and we have exhibited in Hot Wax Records, Brulee Bakery, Sugar Shack, the Sugar Cube, and the EPCOR Centre and Untitled Art Society +15 window galleries. Explore more of our works at: ucfk.wordpress.com

Tuesday, January 27, 2015

DOCUMENTATION: Marvels of the Ages

Documentation of Robyn Moody & Denton Fredrickson's Marvels of the Ages Calling Forth Lost Spirits of Information

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)